CATCH THE WAVE OF READING

CATCH THE WAVE OF READING

CATCH THE WAVE OF READING!

|

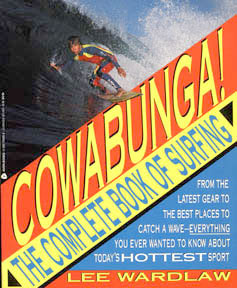

Cowabunga! Avon Books |

“A comprehensive introduction to the sport that starts with the first Polynesian surfers and ends with a look at new technologies. A useful resource for both veterans and beginners.” – School Library Journal An American Library Association “Quick Picks for Great Reads” |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

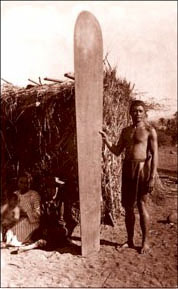

Excerpt from Chapter 2 Tree Trunks and Wili Wili You’re ready to buy your first custom-made surfboard. You hustle down to the local surf shop and talk to the shaper about designs. You discuss board length, shape, color and price. “I’ll get started right away,” the shaper says, after you make your final choice. “Your board should be ready – “ he glances at the calendar “ – in about a year.” A year?! Hardly. Today, even the busiest manufacturers can make a custom board in a few days. But if you were a king or chief living in ancient Hawaii, the royal craftsmen might work a whole year to create a board for you. This is because each board had to be carefully carved by hand. Surfboards (pa’pa he’enalu) were an important part of the Hawaiian culture. Everyone used them for both travel and pleasure. They also had religious significance, and were revered because they joined man and sea. All boards, no matter how crude, were always treated with honor and respect. Kahuna even performed special rituals or ceremonies as a new board was created.

To make a surfboard, a team of men would hike into the cold highlands to choose a tree. After they selected one, the kahuna would place a red fish called a kumu at the base of the trunk. The tree was then cut down and a hole dug in the ground at its roots. Surf-building prayers and blessings followed, and the kahuna moved the fish into the hole as an offering of payment to the gods. Next, the craftsmen would trim off the branches, then chip and chop the wood into the basic size and shape desired. This was done with a stone or bone adz, an ax-like tool with a curved blade. The board was then carefully pulled to the beach and placed in a canoe house, ready for the final shaping. The shaping process often took long, tedious weeks. Again, craftsmen worked entirely by hand, using stone or bone tools to cut and scrape the wood. Next came the staining process. Often, craftsmen applied charcoal or ashes to darken the board. Usually they preferred to use pounded bark or the juice from banana buds and ti plants, because these produced a glassy, lacquer-like shine. Afterward, oil from the kukui nut was rubbed into the wood to repel water.

Some Hawaiians liked to bury their boards in mud. This is thought to have sealed the porous surface of the wood. Again, after the mud dried and hardened, oil was rubbed into the board for waterproofing. At last the surfboard was ready for use. Before placing it in water, the kahuna performed one final ceremony, dedicating the board with special prayers. The royal craftsmen also took part in this ritual. They had a right to feel proud: each finished board was sleek, shiny and beautiful. Over time, Hawaiians thought a good board took on a spirit or personality. These boards became prized possessions, and their owners took great care to make sure the boards would last many years. After each surfing session, a surfer would dry the board in the sun, then rub coconut oil into its surface to further protect and preserve the wood. At home, the board would be wrapped in cloth and hung in a safe place.

Text excerpt copyright Lee Wardlaw, 1991 |

|

|

|

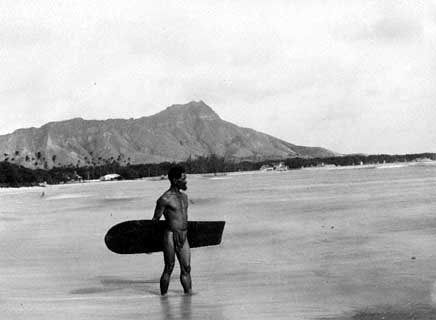

Surfing History Trivia from Cowabunga! No one knows exactly when the sport of surfing began.

When the Polynesians settled in Hawaii

Thomas Edison, inventor of the light bulb and phonograph,

In the spring and summer of 1907,

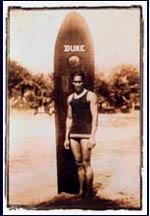

The Father of Modern Surfing, In the early 1920’s,

Tom Blake invented the first hollow surfboard in 1926 During World War II, Velcro, now used on all surboard leashes,

In November 1957, Cool Surfing Links

|